Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

Summer 2017 has been a whirlwind season; as usual I haven’t spent very long in one place at a time, although I am now in the middle of a whole 10 days in Manchester! A definite highlight was my trip to Salzburg to take part in Roche Continents 2017, an annual programme put on for 100 students of science and the arts from all across Europe. It was an intense week; our days began at 7.30am with Tai Chi and usually ended at 1am with ‘late night reflections’. Throughout the days we heard talks from a variety of science and arts professionals and took part in performance workshops with Fritz Hauser, group challenges and photography workshops. As the programme is run in conjunction with the Salzburg Arts Festival, we were taken to see and hear some spectacular performances. The first was a relatively rare performance of Grisey’s Les Espaces Acoustiques, led by Maxime Pascal in the beautiful Kollegienkirche. Written between 1974 and 1985, this early endeavour into spectral music presents an ambush of explorations into rhythm, texture and timbre as it gradually evolves from a solo viola piece into a large and powerful orchestra. Hearing this live was beyond any experience that you could expect from a recording, but the melodic, yet satisfyingly aggressive prologue for viola has made its way onto my Spotify playlist.

Other personal high points were hearing Schostakowitsch’s Symphonie No. 15 in A major op. 141 by a fantastic ensemble and seeing Reimann’s Lear at the Felsenreitschule, a venue most famous in my mind from the Sound of Music. Possibly my favourite was William Kentirdge’s production of Berg’s opera Wozzeck. The artistic approach was so captivating that I was inspired to go to two exhibitions of his work during my extra time in Salzburg and I will be on the look out for his name in the UK.

After a quick detour to beautiful Munich, I headed back to my normal Manchester/London routine. I’ve also been to two great conferences recently. The first was the 11th Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain Conference held at Birmingham University. I was slightly too disorganised to apply to present, but I was excited to attend as the programme was filled with scholars who in my mind are A-list celebs, such as Christina Bashford and Derek Scott who both gave keynotes. Among the many great papers, there was a particularly interesting panel session about a relatively new project, Sounding Victorian, which combines a group of digital projects using sound as an experiential way of conceptually thinking through archives that document lived experiences of literature and music in nineteenth-century Britain. Much of this venture is relevant to my research about the women musicians of South Place. ‘Sounding the Salon’ explores musical salons and ‘at homes’ as an alternative to public concerts, partly focusing on women’s participation in the events and the songs themselves, many of which were written by women such as Maude Valerie White and Liza Lehmann who were also popular at South Place. Sounding Childhood is focused on children’s religious music and social music and features reproductions of scores and recordings. Alisa Clapp-Intyre’s research surrounding the Christian hymn-books for children provide an excellent comparison to the several children’s hymn books that Josephine Troup wrote for the Ethical societies. One summary of Clapp-Intyre’s work is that: ‘Hymns challenge and empower children, placing deep theology and rich poetry within the grasp of children’. I would argue that the same can be said for Troup’s hymns if you replace the word ‘theology’ for ‘morality’. A more thorough look at the music will also determine whether Troup’s attempt to write more intellectual music for children was successful in comparison to the most popular religious hymns sung by children throughout the nineteenth century.

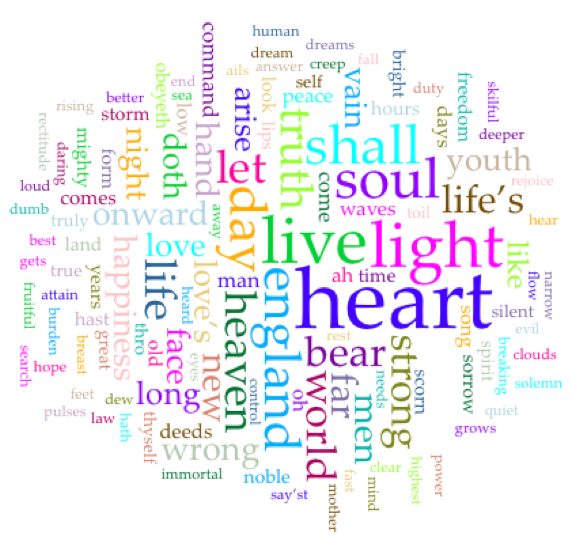

A key aspect of Sounding Victorian the focus on its form as a digital resource. In her introduction to the project, Phyllis Weliver discussed some of the digital tools that she has used for her work on music and Victorian literature. One that immediately struck me was the use of Voyant Tools to perform text analysis, which I thought would be a useful and insightful way of analysing the hymns as texts rather than music. As typing out hymns is quite time consuming, I have initially tested this by typing out the first hymn composed by Josephine Troup from each ‘section’ of Hymns of Modern Thought. This hymn book, like many of the Ethical hymn books, is divided by themes such as ‘love’, ‘truth’, ‘life’, ‘death’ etc. I hoped that my method would highlight the commonalities across each of these themes, as well as give an indication about the type of poetry and subjects that Troup was inspired to turn into music.

One of my immediate observations was the prominence of words that you would expect to see in religious hymns: ‘heart’, ‘light’, ‘soul’ and are all words linked to God and religious sentiment. ‘Heaven’ is particularly interesting as it is the most conspicuously religious, however in context it is used to contradict Christian ideas of heaven as a destination for the afterlife, with lines such as ‘so to live is heaven’ and ‘goodness is my only heaven’ – an idea that was clearly of great importance. However, these most regularly occurring words, along with ‘live’, ‘strong’, ‘truth’, ‘day’, ‘life’, ‘love’, ‘happiness’ and ‘new’, are all very positive words and I would be interested to compare this to a religious hymnbook, where I predict words such as ‘mighty’ and ‘power’ might become more prominent.

I’ve also recently returned from the First International Conference On Women’s Work in Music held in Bangor – long over due if you ask me! This four-day event was packed with a diversity of papers ranging from recovering forgotten nineteenth-century composers to looking at the position of women in the field of electronic music. Jessica Duchen gave a passionate keynote address focusing on the current state of women in music and Sophie Fuller’s keynote was so full of relevant ideas that I managed to scribble four pages of notes. There was an abundance of great lecture-recitals and concerts featuring some rarely heard music by composers such as Grace Williams, Elizabeth Maconchy, Morfydd Owen and Rebecca Clarke, along with premieres of works by Eleanor Alberga and Dilys Elwyn-Edwards. A highlight for me was a brilliant performance of Judith Weir’s one-woman, three-act, 10-minute, unaccompanied opera called ‘King Harald’s Saga’ performed by Elin Manahan Thomas. Unfortunately I can’t find any examples on youtube that match up to her execution of the work, which was perfectly timed, well acted and beautifully sung. It’s definitely a performance that I will remember.

I’ve also recently returned from the First International Conference On Women’s Work in Music held in Bangor – long over due if you ask me! This four-day event was packed with a diversity of papers ranging from recovering forgotten nineteenth-century composers to looking at the position of women in the field of electronic music. Jessica Duchen gave a passionate keynote address focusing on the current state of women in music and Sophie Fuller’s keynote was so full of relevant ideas that I managed to scribble four pages of notes. There was an abundance of great lecture-recitals and concerts featuring some rarely heard music by composers such as Grace Williams, Elizabeth Maconchy, Morfydd Owen and Rebecca Clarke, along with premieres of works by Eleanor Alberga and Dilys Elwyn-Edwards. A highlight for me was a brilliant performance of Judith Weir’s one-woman, three-act, 10-minute, unaccompanied opera called ‘King Harald’s Saga’ performed by Elin Manahan Thomas. Unfortunately I can’t find any examples on youtube that match up to her execution of the work, which was perfectly timed, well acted and beautifully sung. It’s definitely a performance that I will remember.

I did actually give a paper during this conference, but I think I’ll save some of that for another day… However, it was a pleasure to speak in the same session as Susan Elliott and Maren Bagge, who presented excellent papers on ‘Women Composers and the Proms: The First 100 Years’ and ‘Women Song Composers and the London Ballad Concerts’ respectively. Both Susan and Maren provided excellent tables and graphs of their findings – definitely something I can work on.

Best get on with some work as this week is the official start of my third and (supposedly) final year… eeeek!