Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

This post was written by Conway Hall Library & Archives volunteer, Paula Przybylowicz, who has been researching the pacifist ethics of our namesake Moncure Conway.

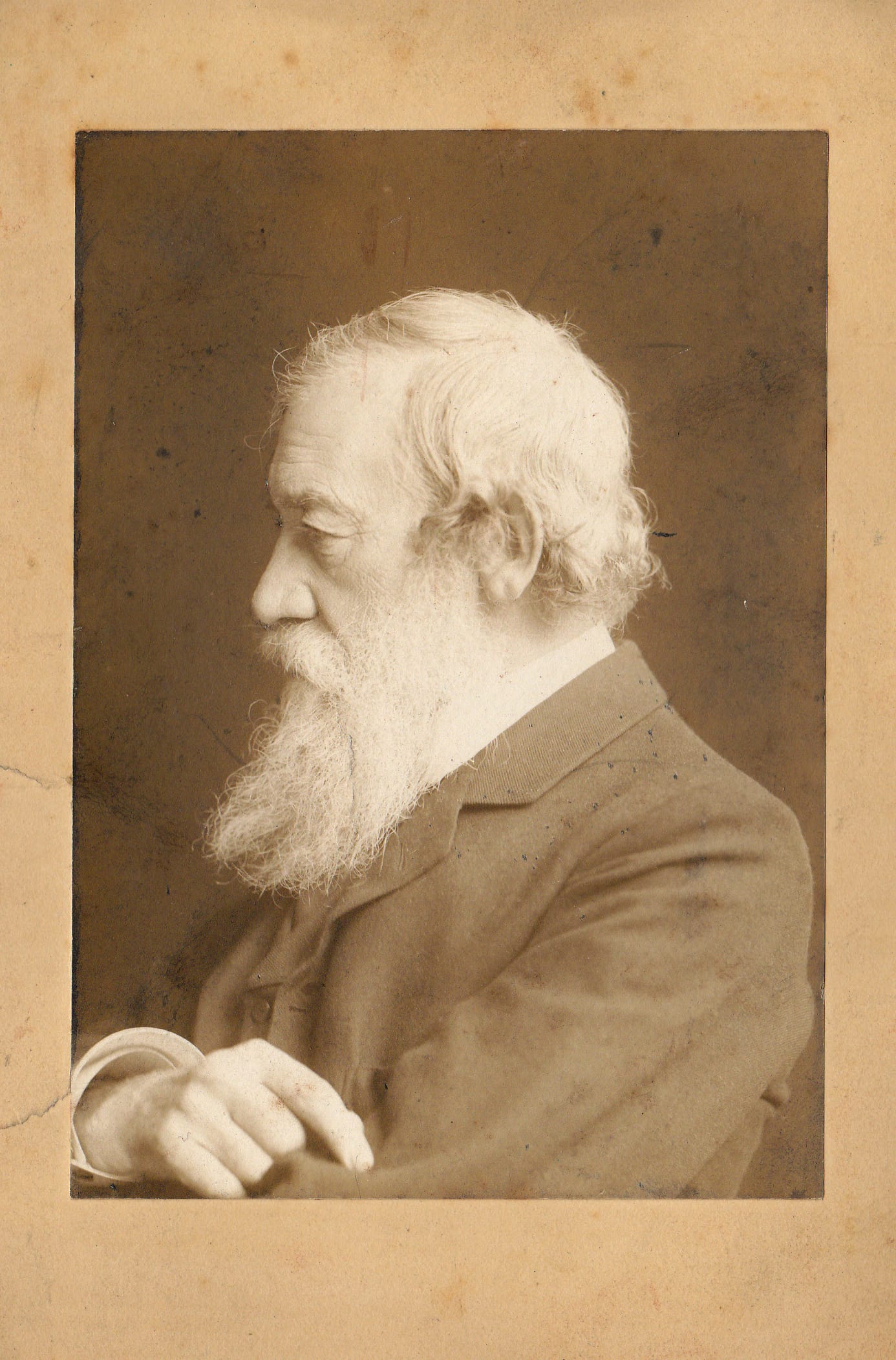

Moncure Conway (1832-1907)

Throughout his life, Moncure Conway’s moral convictions evolved to become not only ethical values but also deeds that encouraged social change. In this sense, his life perfectly incarnated the Shakespearean motto that heads the main hall of the institution he gave his name to—Conway Hall—: “To thine own self be true”. In fact, Conway considered self-truthfulness to be “the most complex of ethical problems”. He was raised in Virginia, yet he was against slavery. He was a Unitarian minister sceptic about the miraculous nature of Jesus and referred to himself as a “pre-Darwinite evolutionist”. He thought that women should be given “freedom and occupation” and that their salaries were unjust compared to men’s. But one thing Conway felt was most worth fighting for was peace.

Conway already had “extreme peace principles” in his youth. In 1852, he wrote a plea for peace inspired by Thomas Carlyle’s French Revolution. Back then, he had not exposed his position as an abolitionist publicly. Still, very soon, this issue and his opposition to war acquired more relevance as the beginning of the American Civil War approached. Conway’s pacifism meant he rejected any project of abolition by violent means.

After a period as a Methodist circuit rider, Conway moved to Washington, where he was a minister of the Unitarian Church. During that period, between 1855 and 1856, Conway’s discourse became more political. On January 26th of 1856, he delivered The One Path; or, the Duties of North and South, a strongly political sermon which was also printed and distributed as a pamphlet. In it, Conway appealed to conscience, to mutual concession not for political advantage but as a moral necessity. If North and South were firm in their position on slavery, Conway claimed, they should not continue to be united. Although he rejected slavery, thus sharing the North’s aim in this sense, he believed that separation of both sides was the only way to avoid perpetual discord.

At the start of the Civil War, Conway joined President Lincoln to discuss anti-slavery and war, having gained recognition as a key abolitionist. He recognised Lincoln’s qualities, yet he considered that the president had full individual responsibility for the blood of the conflict. A year after his arrival at the capital, Conway’s preaching about slavery as a moral issue had led to his dismissal and he moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. It was not the last time that he lost public support because of his values.

In 1863, Conway’s efforts as a campaigner led to the abolitionist leaders sending him to London to represent their interests in England. Once again, his moral commitment translated into a wrong move for his career. While in London, Conway sent a letter to the Confederate representative James Murray Manson “on behalf of the leading antislavery men of America”. He offered to preserve the Confederacy after the war if the South accepted the emancipation of the slaves. Manson, of course, rejected the proposal. Both men’s correspondence was exposed in the press, and a condemning public response followed. As a consequence, Conway lost the abolitionists’ support, and his influential position in the American anti-slavery movement was substantially damaged. From then onwards, Conway continued to professionally and intellectually develop in Europe, where he spent most of his adult life.

Paula Przybylowicz

- Tagged:

- Moncure Conway

- pacifism