Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

This post was written by Conway Hall Library & Archives volunteer, Paula Przybylowicz, who has been researching the pacifist ethics of our namesake Moncure Conway. This is the second part; part one can be found here.

By 1863, at the age of 31, Moncure Conway had served as a circuit rider, preached against war as a Unitarian minister in Washington, and become a renowned figure of the abolitionist movement in America. That year, he was sent to England to represent the abolitionist leaders, a mission which, nonetheless, ended when he surpassed his responsibilities by negotiating with a Confederate representative, James Murray Mason.

After the Mason incident, Moncure Conway travelled to Venice, where he joined his wife and children, and soon after returned to America. By that time, Conway’s pacifist principles had gotten stronger. He was exempt of military service because of his poor sight, but ultimately “would sooner be shot than shoot anybody”. For him, Southern slaves were the “only innocent party”, and he condemned the fact that they had been forced into a conflict for the interests of white, free men. After a short period in his native country, Conway decided that as long as America were militant, there would be no place for him there, so he and his family moved to London, where he took up his role as minister of South Place Chapel, now Conway Hall.

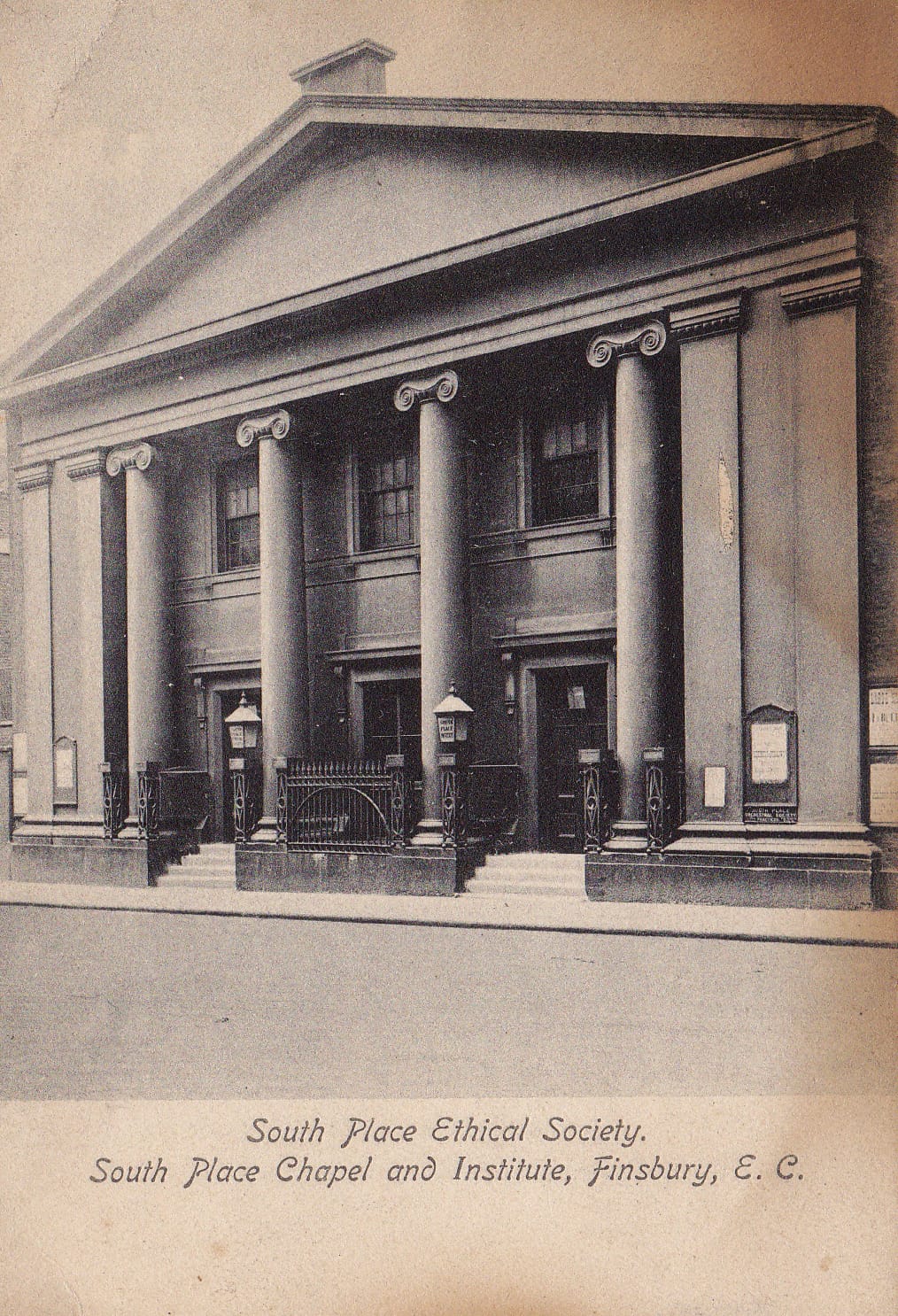

South Place Chapel, the former home of the Ethical Society during the leadership of Moncure Conway.

Conway’s life in London orbited around his ministry at South Place Chapel (the Ethical Society’s previous home), writing and publishing, and his involvement in English intellectual circles. He also participated in the Peace Society in London and co-operated with its leader, Hodgson Pratt, who was also the president of the International League of Peace and Arbitration in Europe. Between 1870 and 1871, Conway worked as a war correspondent during the Franco-Prussian War, an experience which cemented his anti-war beliefs.

In 1897, following his wife’s death, Conway settled in Paris. As happened with the Civil War, he didn’t want to be engaged in a belligerent country and, at this time, the United States was fighting with Spain for the independence of Cuba. In France, Conway continued to work for the project of peace. His writings were distributed at the Universal Peace Congress at Paris, in 1900, where he proposed a plan to secure an unofficial arbitration by the most prominent jurists and publicists of all nations on disputes that threatened peace. He believed that no war would happen if decided in a fair trial by a tribunal. On this proposal, he wrote:

“Although aggressiveness and blood-thirst seemed “universal” in several nations, there is distributed through these and all nations a moral and peaceful nation, and my aim was to organize this moral nation sufficiently to reinforce the peace party in each country threatening war, by bringing to its aid the judgement of the best representatives of civilization as to the path of justice” [1].

Conway died in 1907 in Paris, at the age of seventy-five. He had carried with him a fight for peace wherever he travelled. For him, it was a matter of shared responsibility among all humans and all nations. Even his autobiography, published in 1904, concludes exhorting the reader to work, as he did, for peace:

“Implore Peace, O my reader, from whom I now part. Implore peace not of deified thunderclouds but of every man, woman, child thou shalt meet. Do not merely offer the prayer, “Give peace in our time”, but do thy part to answer it! Then, at least, though the world be at strife, there shall be peace in thee. Farewell!” [2].

Paula Przybylowicz

[1] Conway, Moncure Daniel (1904). Autobiography, Memories, and Experiences. Volume 2. Cambridge (Massachusets), The Riverside Press. p.449.

[2] Idem. p. 454.

- Tagged:

- Moncure Conway

- pacifism